HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Ever since the Key West Agreement of 1948 (pet name for the

policy paper titled “Function of the Armed Forces and the Joint Chiefs of

Staff”), which limited Army aviation activities to reconnaissance and medical

evacuation purposes and put severe weight restrictions on any aircraft. The

Army maintained that the Air Force was too strategic (ie nuclear) minded

and not giving enough attention to the tactical and logistical needs of the

Army. As a result the Army often pushed

the envelope of the agreement limits, citing the need for better transport and

close air support assets.

To try and smooth the troubled waters, in 1952 a memorandum

of understanding was reached between USAF Secretary Thomas Finletter and US

Army Secretary Frank Pace that removed all weight restrictions on helicopters

operated by the Army. It did, however;

place an arbitrary 5,000-pound weight restriction on any fixed-wing aircraft.

During the late 1950s, the Army Aviation Test Board and the

Aviation Combat Developments Agency (ACDA) began to jointly explore the

feasibility of using Army-operated fixed-wing jet aircraft in artillery

adjustment, tactical reconnaissance, and ground attack roles. In early 1958 three Cessna T-37As were

borrowed from the Air Force for a one-year evaluation program dubbed

Project LONG ARM. The Army’s evaluation

found the T-37 to be ideal for their needs, and the Aviation Board and the ACDA

recommended quantity procurement of the type.

But the Air Force, citing the Key West Agreement, put pressure on the

Army, and eventually the program was dropped.

But the Army wasn’t done, the battle may have been won by

the Air Force, but the war had just begun.

In 1961 the Army Aviation Test Board and the ACDA once again stirred the

pot by trying not one, not two, but three jet aircraft types in a competitive

“fly-off”. The aircraft chosen were the

Northrop N-156 lightweight fighter prototype, The Douglas A-4 Skyhawk, and the

Fiat G.91. Ostensibly these aircraft

were to be used as tactical reconnaissance and target spotting, and artillery

adjustment roles, but it was hard not to notice that each of these aircraft had

offensive weapons capability, which was clearly contrary to the Key West

Agreement. Again the Army’s tests were

in vain because Air Force pressure again forced the Army to scuttle its plans

for jet fixed-wing aircraft.

Meanwhile, the Army had acquired a fleet of fixed-wing

aircraft ranging from the Piper L-4 (730 pounds empty) to the DeHavilland-Canada

U-1 Otter ( 4,431 pounds empty). All of

these aircraft easily fit under the limitations of the Pace-Finletter MOU of

1952. Air Force apprehension rose when

the Army in 1962 awarded a contract to DeHavilland- Canada for the CV-2 Caribou (later the C-7). This aircraft was exactly what the Army

wanted, a rugged and reliable aircraft that could haul nearly 4 tons of cargo

or 40 passengers into and out of the roughest forward airfields. The Army quickly made it the poster child of

Army Aviation. Oh, did I forget to

mention that it weighed 16,920 pounds empty? Even though it was a tactical cargo aircraft, which was supposedly taboo, the Army justified it by a new concept the Army was incorporating called

“Air Mobility”.

By now you are wondering “What has all this got to do with

the Phantom II?” Be patient, I’m almost

there.

Naturally, the Air Force was a bit peeved. The Army had not only purchased a tactical cargo aircraft, it had armed helicopters (which the Army was not supposed to do), and to add salt to the wound, the US Army talked

the US Marine Corps into sponsoring a battlefield observation aircraft from Grumman,

both sides knowing full well that the Navy would never buy it for the

Marines. But as a result, the Army

“found” this nice “little” Marine aircraft that nobody wanted and decided to be

nice and order a bunch. Enter the

Grumman OV-1 Mohawk. It was a bit heavy at around 11,500 pounds empty, but it was the perfect battlefield observation aircraft and was really needed in a hot spot that was heating up called Vietnam. It even had pylons that could carry fuel tanks (not to mention the odd gun pod or missile launcher). The Air Force was not amused.

Finally, we get the Johnson-McConnell Agreement of 1966,

where the Army agreed to turn over its fleet of Caribous and the newer Buffalo and pursue their development of VTOL aircraft on a joint basis with the Air

Force. The Air Force agreed to let the

Army continue to develop and operate rotary wing aircraft, without weight

restrictions, and would not interfere with their tactical helicopter operations (even armed helicopters) in support

of the Army’s mission. The one aircraft

that was an exception was the Mohawk which the Army was permitted to continue

to use (It really was a great battlefield observation aircraft with its side-looking radar and other sensors).

Sorry for the history lesson, but it is necessary to

understand the climate into which the McDonnell proposed Phantom II ground support aircraft for the Army was introduced.

THE PROPOSED MCDONNELL

PHANTOM II GROUND SUPPORT AIRCRAFT FOR THE ARMY

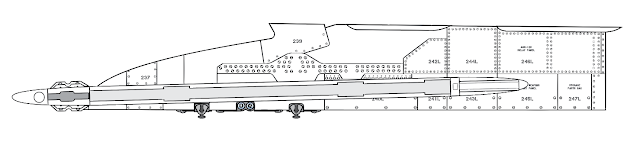

In 1961 McDonnell drew up specifications for two attack

aircraft based on the F-4H airframe. I

don’t know if they ever were presented to the Army, but I assume they were because they are on the books

as Models 98DA and 98DB with the US Army as the proposed customer. This would have been about the time of the evaluation fly-off of the N-156, A-4, and the G.91, so I imagine that McDonnell didn't want to get left out if the Army was going for jet aircraft.

MODEL 98DA

The Model 98DA was a model F4H-1 modified for the Army

ground support mission. It was offered in two versions - G-1 and alternate G-1

with changes as follows:

- Two-place aircraft.

- Remove all electronic equipment items and replace them with close support equipment to provide visual delivery of ground support weapons and visual lay-down capabilities.

- Replace the single main landing gear tire with dual 30 x 7.7 tires.

- Deactivate the wing fold and remove the catapult and arresting gear.

- Remove Sparrow III missiles and supporting equipment and electronics.

- Remove equipment refrigeration package for equipment cooling, utilizing cabin refrigeration unit to also cool equipment.

- Add cartridge starters and battery.

- Replace the present arresting gear with a lightweight hook.

- Add IFR boom receptacle.

- Powered by two General Electric J79-GE-8 turbojet or Allison AR-168-18 (Allison built Rolls Royce Spey RB-168) turbofan engines.

- (Alternate G-1 only) Add one M-61 Vulcan aircraft cannon with 930 rounds of 20mm ammunition.

MODEL 98DB

The Model 98DB was the same as Model 98DA but further

modified for the Army ground support mission with changes as follows:

- Single-seat Aircraft

- Remove the rear seat and all associated controls, instruments, and equipment. (Space available for equipment growth and/or reconnaissance capability)

- Remove the rear canopy glass and replace it with sheet metal.

- Remove the rear canopy electrical and jettison equipment and modify manual controls to open and close the hatch.

- Eliminate Central Air Data Computer (CADC) and flight control group equipment.

- Remove IFR Probe and all associated equipment.

- Remove variable bellmouth from engine duct, and keep bellmouth controller to control variable inlet ramps.

- Powered by two General Electric J79-GE-8 turbojet engines.

THOUGHTS

It is evident that these proposed aircraft were clearly a much

stripped-down attack version of the Phantom II.

Almost all of the air-to-air capability has been stripped away. Some of the proposed changes indicate

that this wasn’t intended to be a high-speed aircraft. The dual main gear, obviously intended to

help the aircraft operate out of rough, forward area airstrips, would have hung

out into the airstream, and even if fairings would have been utilized to blend it into the

wing, they would have had a performance hit.

Eliminating the CADC and bellmouth would also have curtailed any

high-speed / altitude flight. This

aircraft was intended to be a mud-fighter – a low-altitude, subsonic aircraft

that could manually deliver an impressive load of munitions on a given target.

I am sure that the Army didn't show a lot of interest because, even in the stripped-down state presented by these proposals, the F-4 was just too much of an aircraft both weight-wise and complexity to operate out of primitive forward area airstrips. Maintenance would have been a headache, and even with the dual main wheels, I am sure it would sink into any soft soil it would come in contact with. The T-37, which was the early favorite, would have probably served the Army well in its intended role. But in the end the Army didn't pursue any jet aircraft, and the Air Force won the war in the end.

REFERENCES:

- US Army Aircraft Since 1947, by Stephen Harding

- Note by the Secretaries to the Joint Chiefs of Staf- Functions of the Armed Forces and the Joint Chiefs of Staff – Reference J.C.S 1478 Series, dated 21 April 1948

- A History of Army Aviation: From Its Beginnings to the War on Terror, by James Williams

- Tactical Airlift. United States Air Force in Southeast Asia, by Ray Bowers

- McDonnell List of Proposed Models, dated 1 July 1974

REVISIONS:

28 November 2013 – Initial Post